The Moral Compass of Cricketers

- The Cricket Keeper

- Aug 4, 2025

- 10 min read

04.08.2025

When I first moved to the UK, my cricketing sense of right and wrong ran head‑first into someone else’s. I’d been playing for around eight years by then, and in one of my first university league matches I went in at three on a grey, heavy afternoon. The ball was hooping. I nicked one behind, they went up, and the umpire said not out. In my head that was the end of it. Where I grew up, you respect the decision. If you choose to walk, that’s your call; otherwise, you stay. I stayed. The close fielders started celebrating anyway, waiting for me to wander off. I didn’t. A few comments flew my way, nothing vicious, but pointed enough, and I carried on, only to be out soon after. Back in the changing room my teammates asked why the fuss if I hadn’t hit it. I said I had. “You cheeky little…,” someone laughed, and I realised I might have stepped on an unwritten line I didn’t know existed.

I forgot about it until we were in the field. Our captain was bowling when an opposition batter feathered one. We appealed, the umpire said not out, and the batter stayed put. The captain spun around and shouted at me, “This is on you!” Right there, mid‑over, in front of everyone. I stood at mid‑off wondering how a university game, not exactly the top tier, had turned into a public telling‑off. I checked with another teammate who, like me, wasn’t from the UK. Where we came from, she said, if the umpire doesn’t give it, it isn’t out. Simple.

What stuck with me wasn’t the decision. It was the choice. If walking is your principle, why abandon it the moment someone else doesn’t share it? If you prize a value, isn’t the test whether you keep it when it’s inconvenient, whether you walk even when the batter at the other end wouldn’t? A couple of years later I asked another teammate about it. Her take: “If I like the team, I’ll walk. If I don’t, I won’t.” That felt like a shaky compass; one that points wherever the wind of feeling happens to blow.

That day was my first lesson in how differently cricket’s “spirit” is taught and lived. Culture shapes it. Coaching shapes it. So do friendships, grudges, and the mood of the match. But if this game keeps asking players to police themselves, then whose code are we following, the one we were raised with, the one our teammates demand, or the one that suits the moment?

On Mankads, pressure, and the strange burden of being “right”

Let’s talk about the Mankad.

It’s one of the most divisive acts in modern cricket, technically legal, but constantly debated. And I remember almost being Mankadded myself, about a year after that earlier walking incident. While I was on the non-striker’s end, I’d been taking a few extra steps outside my crease. I struggle with a couple of injuries from time to time, so I do sometimes try to get a slight head start when running between wickets. That said, it’s not an excuse. I was leaving my ground too early, and the bowler was well within her rights to notice.

She pulled up mid-delivery, turned, and took off the bails. Appealed. Then, almost as quickly, she withdrew. And that was that. I carried on.

But in that moment, my only thought was: she was absolutely right to do that. She didn’t give me a warning, but she didn’t need to. I was clearly backing up too far, and I knew it. I’ve never agreed with the Mankad. I wouldn’t do it myself. I wouldn’t appeal for it. But I also couldn’t pretend I hadn’t been pushing the limits. The blame, if any, was mine.

I’d batted through to the end of the innings and she came up to me straight away. “I’m really sorry,” she said. I was confused at first—sorry for what? The incident had slipped my mind completely. It hadn’t even registered as dramatic. She apologised, and I told her not to worry.

But it stayed with me, later. I started wondering, was that apology genuine? Or was it guilt? A bit of post-match diplomacy maybe? In the moment, it felt sincere, so that was my conclusion on the matter. And the more I thought about it, the more I realised how much of the so-called drama we see in the media might just be a result of players being locked into the match, focused, reactive, caught in the pressure. Then they walk off, let it go, and it’s forgotten. But the rest of the world won’t forget. A quick decision becomes a talking point. A rulebook appeal becomes a character judgment.

And for the record, I’m still not a fan of the Mankad. Because at its heart, cricket is about bat and ball. One trying to outsmart the other. When you Mankad someone, that exchange doesn’t happen. The ball isn’t bowled. The batter isn’t tested. It removes the core contest of the game.

I’ve said this before, but one reason associate nations struggle to catch up with full members is the volume of skill and infrastructure required to succeed in cricket. Unlike football, where you can, in theory, shut out a top player and stop them from touching the ball, you can’t stop someone like Virat Kohli from facing the ball. If you don’t bowl, you lose. If Pat Cummins is steaming in, you can’t say, I don’t want to face him. That’s where the skill gap plays out. And that’s why taking the bat out of the equation in a key moment feels like the wrong call.

Think back to the famous Mankads. Most of them, from memory, happened in pressure situations. Jos Buttler being run out by Ashwin in the IPL; Buttler was set, cruising, and the bowling side was under pressure. U19 World Cup semi-final—West Indies vs Zimbabwe. Final over, scores tight. Instead of bowling the ball, the bowler whips off the bails. Charlie Dean and Deepti Sharma; again, the final over, the tension high. It’s rarely done when the game is relaxed or one-sided. More often, it feels like the bowler is collapsing under pressure, trying to wrestle back control without risking another contest with the bat.

And it’s not even a clean fight. The non-striker isn’t even facing the bowler. It’s like tapping someone on the shoulder and punching them when they turn. You might win the point, but did you win the battle?

And then there’s the aftermath. When the incident’s done and the noise begins. Suddenly, everyone’s got a take. Some defend it because they’ve done it themselves and want to justify it. Others do it to support a teammate, a friend, a partner. Even if they wouldn’t make the same call, they feel the need to back their side. And once it’s said, especially on TV, no one wants to take it back. Because the internet will never let you forget.

That’s what I find hard to sit with. Why can’t we just admit: I made a mistake? Why can’t players say, I was in the heat of the moment, I did something I wouldn’t usually do? There’s no shame in that. But too often, pride takes over. The media grabs hold. Strangers start yelling online. The idea of a moral compass, of holding to your values, gets drowned out by noise.

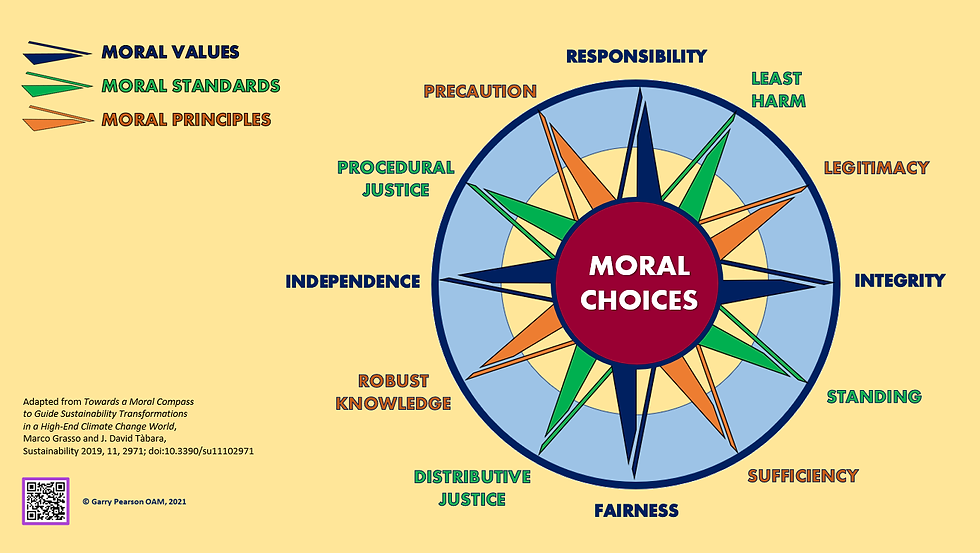

So, where does that moral compass come from? Where should it point, when the crowd’s screaming, your team’s on edge, and everyone has a camera on you? I’m not sure. But I do think it has to come from you, and not just when it’s convenient.

When spirit meets stumps: Stokes, centuries, and choosing your side

The most recent debate around the “spirit of the game” came during Day 5 of the fourth Test between England and India. With the match all but done, Ben Stokes reportedly asked Ravindra Jadeja and Washington Sundar to call time. England weren’t going to take the remaining wickets, and with their bowlers having worked themselves into the ground on slow, lifeless pitches, Stokes wanted to give them a break. Jadeja and Sundar declined, they were closing in on 100s.

As a neutral observer, I could genuinely see both sides.

On one hand, it was the final day of a draining Test. England’s quicks had been pounding the turf with little help from the conditions, and it’s fair for a captain to protect his bowlers. This wasn’t about vanity; it was about welfare. Stokes later said something along the lines of, “You’ve done your job for your country and that should be worth more than a hundred.” And in some cases, I agree. There are innings of 40 or 50 that carry more weight than a century. We’ve seen it.

But from Jadeja and Sundar’s perspective, their position was equally valid. They had rescued India from a near-hopeless start at 0 for 2. They had fought back against the odds, with the added pressure of knowing Pant was unavailable. They earned the right to stand firm. Having done the hard work, why should they be asked to stop short of the milestone? Why not push on?

That tension—between team fatigue and individual reward—boiled over. The English players grew frustrated, and things got heated. Some reportedly asked sarcastically, “How much more do you want—another hour?” And when it became clear they wouldn’t be walking off, Stokes turned to part-timers like Harry Brook and Ben Duckett, as if to say, “Fine. You want your hundred? Here—take it off these guys.” Whether or not that was his exact motive, it came across as a way to cheapen the achievement. I didn’t agree with that at all.

Bumble and Michael Vaughan discussed it on their podcast, and one of them asked: “Would you still want that hundred, if it came off part-timers?” The answer was yes. You’ve done the graft. You’ve survived the spells. The hundred is a reflection of that entire innings, not just the last few runs. And I agree.

There were two sides to this incident. Stokes had every right to be tired, even upset. But the batters had every right to stay. In truth, it was a trivial issue that spiralled far beyond what it needed to be. Once the match ended, that should have been that. Instead, articles poured out, many of them unfairly skewed. Some painted Stokes as entitled, suggesting England believed they alone defined “sportsmanship,” and that the moral compass of the game should bend to them.

That take bothered me. I didn’t like how it was framed, but I did agree with one underlying point: not everyone plays cricket the same way. And they shouldn’t be expected to. People come from different cultures. What’s seen as noble in one country might be irrelevant in another. What’s disrespectful to you might be normal elsewhere. It doesn’t make one version more authentic than the other. The only line, for me, is that nobody should be getting hurt, physically or mentally. Everything else is just part of the game.

The “spirit of the game” is not some fixed doctrine. It’s just about how we treat each other on the field. I’m not going to bend my values to suit someone else, but I can still respect where they’re coming from. The right and wrong of sport is not the same as the right and wrong of life. We need to stop pretending that it is.

Take, for instance, the Carey–Bairstow incident during the Ashes. When I first heard about it, I didn’t even have an opinion. It just seemed obvious: if you supported England, you backed Bairstow. If you supported Australia, you backed Carey. It wasn’t complicated. And again, it came down to presence of mind. The umpire hadn’t called “over.” Bairstow walked out of his crease without checking. Carey noticed, and he acted. Was it a little cold? Maybe. But no laws were broken.

Let’s flip it. If a ball is rolling away from the keeper and the fielders aren’t paying attention, a batter will often steal a cheeky single. That’s seen as smart cricket, sharp running. So why is it different in reverse?

There are layers to every one of these moments. Your reaction usually depends on where you’re standing - on the field, or in your living room, or in your own cricketing upbringing. The important thing is to stay grounded. Understand that not everyone sees the game the same way. And that’s okay.

The True North of Cricket’s Moral Compass

At its core, a strong moral compass in cricket comes down to one word: respect. Respect for your opponents, for the umpires, for your own team, and for the game’s values is the bedrock of the sport’s fabled “Spirit of Cricket.” That means playing hard and fair, accepting the umpire’s call, and never taking an unfair advantage, especially when you know you could get away with it. These principles don’t show up on a scorecard, but they’re understood across countries and cultures as part of what keeps cricket honest.

Cricketers who hold onto these values earn something that numbers can’t measure, the admiration of teammates, opponents, and fans. Winning matches is one thing. Winning the respect of people who watch you play is another. One powerful example of this came when New Zealand’s Daryl Mitchell refused to take a single after colliding with the bowler during a tense World Cup semi-final chase. He could’ve kept running. Instead, he stopped. In that moment, he chose fairness over gain, and earned the respect of the cricketing world.

Players like Mitchell show us that upholding integrity matters more than sneaking an extra run or wicket. These moments of character stay with us because they shape the way people feel about the game.

In the end, a cricketer’s moral compass has to be personal. It’s your own true north, something that shouldn’t change just because it’s inconvenient. Whether it’s choosing to walk after edging a ball, staying silent during a dubious appeal, or deciding not to Mankad in a tight match, the real test is what you do when no one would blame you for taking the shortcut. Because in a sport that spans continents, cultures, and worldviews, sportsmanship is the one language everyone understands; a shared currency of honesty, humility, and care.

As Daryl Mitchell once put it: “At the end of the day, it is just a game… and we are very lucky to be able to do that in the right way.” No victory is worth compromising who you are. And no disagreement is worth forgetting that we’re all just trying to play the game in the way we believe is right. The moral compass doesn’t have to match, but it should stay steady. That’s how we keep the game worthy of the love it inspires.

Comments